Riddle Fortnightly No. 9

Of Aug. 11, 2024

Dear Reader,

Put on a pot of tea, get out some biscuits, and fetch your E-ink tablet – it’s time for what we hope might become the pleasant Monday coffee-break ritual of reading another Riddle Fortnightly. In this week’s edition,

- An extremely efficient workflow for time-blocking planning.

- The Riddler, on Grades, Grant Applications, and the paradox of evaluation, as told by a psychologist and an anarchist.

- And of course, the Fortnightly Riddle (this one much easier than the last.) Perhaps you can be the first to solve it.

Thinking Tools: Exceedingly Efficient Time-Block Planning with Reclaim and ClickUp

Apps, tools, and workflows for thinking better with technology.

Time-block planning, the practice of ‘blocking off’ time for tasks on your calendar, is recommended by every time guru there is, from Cal Newport to David Sparks, to (arguably) Martin Heidegger and the Dalai Lama. Likely, most of the benefits of time-blocking derive from having to grapple with which tasks are worthy of your attention, and how much attention they deserve. But that grappling can take an awful long time, what with manually creating calendar blocks and dragging them around inevitable conflicts. What if you could just indicate how long you want to spend on each task, and when you want to be done with it – and have those time-blocks created automatically?

For the past year, I’ve been doing this through a neat collaboration between the following two apps:

- ClickUp- a ridiculously-named but quite flexible project manager. Unfortunately, it’s a web app; there’s limited offline access, and it feels thoroughly non-native. But it has a very nice Trello-like Kanban view which supports deadlines, durations and (most importantly here), a wonderful integration with -

- Reclaim ‘AI Calendar’ - I’ve been using Reclaim for years, initially just to schedule habits (like ‘Exercise’ or ‘Have Lunch’). Unlike standard repeating events, Reclaim can schedule those daily/weekly/biweekly events around other stuff on your calendar – so you have time blocked off for lunch even on that day with a meeting from 12 to 1.

But using Reclaim’s ClickUp Integration, it can apply this same flexible scheduling to tasks from ClickUp, scheduling around your habits and meetings, and becoming more aggressive when scheduling things with impending deadlines. You can restrict Reclaim to schedule in certain sets of hours based on the task’s tag in ClickUp (e.g. in the morning prime if tagged #deepwork, in the afternoon slough if tagged #admin).

The result: instead of your calendar being, by default, empty, it’s auto-populated with a plan for tackling your tasks. The plan usually needs some tweaking (achievable through reordering tasks in Reclaim’s priority view), and you need to be careful with the settings lest Reclaim schedule over your every free minute – but, caveats aside, it’s an exceedingly efficient way to do time-block planning.

Now, although Reclaim is also web-based, you can edit the events it creates in any native calendar app. My favorite is still Fantastical, for its natural language event creation. It works very well with Reclaim’s auto-generated events.

Great Reads

Quotes from ’round the web, collected by our resident spyder: the Riddler, whose grumbled commentary you’ll hear below.

Today’s reads:

- Adam Mastroianni - I wanted to Be a Teacher, but They Made Me a Cop, pub. 2023. A short blog post with inimitable humor. Link

- David Graeber - “The Utopia of Rules”, pub. 2015. A short book/collection of essays with an anthropologist’s take on bureaucracy. Bookshop link

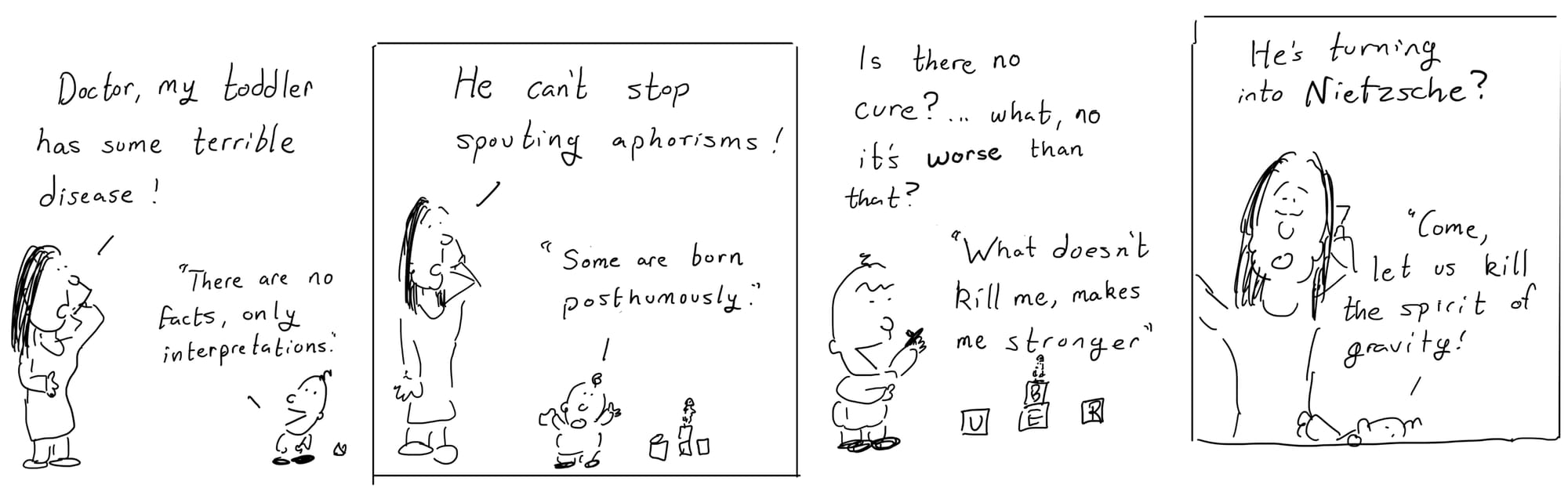

The Riddler had one of those dreams we all have recently, where he found himself in a lecture hall with a professor announcing a midterm exam for a class he had entirely forgotten about. In that sense, he was right – being a grumpy old Riddler millennia removed from his education, he has forgotten most of his classes. But he will never forget the terror of grades.

“How is it,” the Riddler wondered, while brewing his coffee, “that we managed to take the most innocent, child-like activity of learning and smother it so violently with rankings and rules that most people have nightmares about education for the rest of their lives?” Then the Riddler smothered his single shot of espresso with about a gallon of steamed milk and maple syrup, and had the idea. I should start a crusade.

So, yes, welcome to the Riddler’s Crusade against Dumb Stuff in School. First stop, a former post-doc in psychology who ran a blog documenting various amusements in academia as he got this close to becoming a junior-assistant-minion professor, before quitting the academy with the somewhat ardent belief that his blog was a better way to advance human knowledge than the ol’ circus of conferences and grant proposals. Otherwise known as Adam Mastroianni. Here he is on the offensive against grading:

The things that make me a better instructor often make me a worse evaluator, and vice versa. Instruction is collaborative: students want to learn, and I want them to learn, too. Evaluation is adversarial: students want the points, and I have to make sure they don’t get too many. [1]

This is a line of attack the Riddler thinks should be employed more often. The things that make me a better instructor make me a worse evaluator. There’s this panglossian notion that good personal and professional traits can just be stacked on top of each other like condiments on a hamburger – in other words, that one can have it all, and just be “all of the good things”. The Riddler’s nearest equivalent to this is the grade-school food math that proclaims “DELICIOUS PLUS DELICIOUS = DELICIOUS!” No, there are different flavor profiles, and the things that make marshmallows an excellent member of the sweets group mean that the Riddler doesn’t want them in his Szechuan stir fry. To take another analogy, you can’t be both an olympic powerlifter and a gymnast – and not just because you’ll never have time for all that practice.

This, Mastroianni says, is the conundrum forced on teachers. Connect with your students; get to know them as individuals; appreciate their multifaceted abilities – then rank them from best to worst on a somewhat arbitrary numeric scale!

For the students, this gives either the impression that their teachers are hypocrites, or that they have some dissociative identity disorder around grading. For the teachers, this leaves one with the suspicion that the students one is trying to get to know as people view you like some automatic teller machine for ‘A’s, and are just weaseling up to you to get more points in the grading game. Plus, there are a lot of sheer oddities with the system. A lot of Mastroianni’s students tell him that they have diarrhea. “Why am I the guy that people tell when they have digestive distress?” he wonders “Why do we have an education system where it’s reasonable for students to debase themselves in exchange for made-up points?”

Mastroianni muses on the genesis of this grading game, and concludes that it’s industry’s fault. The business world needs applicants to be neatly ranked and professionally certified, and doesn’t have time to verify these rankings and certifications personally. Yes, the rankings are imperfect; yes, a lot of people sneak through the certifications while lacking foundational knowledge – but it’s the system we have (the Riddler’s least favorite English phrase). And somehow the Academy got stuck with the nasty business of doing those rankings.

One solution is to separate instruction and evaluation. Let teachers be teachers and cops be cops. Professional evaluators have the skills and time to ensure their assessments are reliable, unbiased, and cheat-proof; instructors doing evaluation on the side toss a few essay questions into a Word document and hope for the best. If getting evaluated means visiting a police state, it’s better to be a tourist than a resident—spending a month studying for the SAT and an afternoon taking it is miserable, but spending a lifetime in classrooms that double as prisons is even worse. [1]

So, there you have Mastroianni’s solution. Let students through education with as little evaluation possible, where those who have even some potential for succeeding are let through, and only those who are obviously problematic are held back. Then, let the professional world take control of that subjective nit-picky business of ranking students.

The Riddler finds this reasonable. Indeed, he notes that something very close to this system has already evolved under the regime of grade inflation. The Riddler’s contacts at highly-selective colleges tell him that many professors now give ‘A’s to anyone who gives any reasonable effort - and reserve ‘B’s only for egregious offenses like not turning in assignments or skipping the class final. This system has advantages. Professors can (in theory) focus on teaching, without being harassed by grade-hungry students – and students can (in theory) learn the material for its own sake, not out of fear of the midterms.

Of course, that stress formerly spread throughout years of college comes back when taking the MCAT, or LSAT, or navigating the interview labyrinths constructed by companies like Google and Jane Street. But, as Mastroianni would say, perhaps this is preferable: “If getting evaluated means visiting a police state, it’s better to be a tourist than a resident.”

So everything’s fine the way it is? This isn’t what the Riddler wanted from his crusade! He was thinking more along the lines of irredeemable rot, systemic decay, and maybe a return to the Luddites we saw last week. Maybe he should give this next quote to a known anarchist, David Graeber:

The current age of stagnation seems to have begun after 1945, precisely at the moment the United States finally and definitively replaced the UK as organizer of the world economy. [2]

Whoa-oh! That’s more like it.

Graeber, for context, was both a renowned anthropologist and one of the organizers of Occupy Wall Street. The ‘stagnation’ he’s talking of is the general decline of material innovation in the last half century. Americans in the 1950s thought the next millennium would surely bring flying cars, robot servants, and colonies on Mars – and these were only their extrapolations from existing technologies. Add in some unimagined discovery analogous to nuclear energy, and teleportation and Star Trek energy beams seemed eminently possible.

Instead, we have smartphones – little television screens we can use to doomscroll and send telegraphs. Graeber imagines a time-traveler from the 1950s would spend a few minutes examining the smartphone before saying “is that all?” (Arguably, the thing which would now most impress our time-traveler is ChatGPT. “AI! Just like we imagined!” he’d say, before being dismayed to discover that no one has any clear idea how the thing works, how to control it, or why it so often laughably fails.)

Many will ridicule those who lament this lack of progress, or at least ridicule the 50’s era sci-fi nuts who dreamed of it. Technological neonates! Such naiveté! They really thought anything was possible! Others lament the fact that so much less now seems possible, and offer narratives as consolation. Mark Andreessen will tell you that, stifled by government regulation, we’ve forgotten how to “build”, and need to return to “atoms, not bits”. Perhaps it was some kind of wrong turn in the world of policy, or too much policy; conversely, perhaps it was too much unrestricted capitalism; or maybe we just started amusing ourselves to death and stopped dreaming about space.

Graeber thinks the problem is bureaucracy. And not just government bureaucracy; he views corporate bureaucracy and public bureaucracy as near inseparable – part of the same self-perpetuating administrative machine.

Americans do not like to think of themselves as a nation of bureaucrats — quite the opposite, really — but, the moment we stop imagining bureaucracy as a phenomenon limited to government offices, it becomes obvious that this is precisely what we have become. The final victory over the Soviet Union did not really lead to the domination of “the market.” More than anything, it simply cemented the dominance of fundamentally conservative managerial elites – corporate bureaucrats who use the pretext of short-term, competitive, bottom-line thinking to squelch anything likely to have revolutionary implications of any kind. [2]

It was through bureaucracy that America had triumphed in the World Wars. That well-oiled administrative machine – including both the military and Ford’s assembly line – was extremely adept at manufacturing and deploying weapons. And in its post-war zeal, the U.S. tried to apply this same logic to the rest of the world.

The very first thing the United States did, on officially taking over the reins from Great Britain after World War II, was to set up the world’s first genuinely planetary bureaucratic institutions in the United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions – the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and GATT, later to become the WTO. The British Empire had never attempted anything like this. They either conquered other nations, or traded with them. The Americans attempted to administer everything and everyone. [2]

Among those things they tried to administer: the academy. Gone was the old (British) model of patriarchal deans, easily tenured dons and eccentrics like the paleontologist William Buckland and his quest to eat his way through the animal kingdom. The academy would be remade with Modern Management Techniques. Think of the efficiency! Except:

What these management techniques invariably end up meaning in practice is that everyone winds up spending most of their time trying to sell each other things: grant proposals; book proposals: assessments of our students; job and grant applications; assessments of our colleagues: prospectuses for new interdisciplinary majors, institutes, conference workshops, and universities themselves, which have now become brands to be marketed to prospective students or contributors. Marketing and PR thus come to engulf every aspect of university life. [2]

In other words, when the MMTs (Modern Management Techniques) stepped in with dreams of heightened efficiency, their process went something like this:

- Step 1: We have finite [money] and lots of [academics who want it]. It’s currently being allocated based on nepotism/vibes/randomness. The rational thing to do is to create a systematic evaluation that impartially allocates this scarce commodity to align best with our values.

- Step 2: Wow, these [academic projects] are complex. To perform those evaluations, we’ll need to simplify them along a range of objective criteria by creating [grant applications].

- Step 3: Inevitably, the [grant applications] do not perfectly simplify the complexity of the underlying problem. Instead, they create a system that both distorts reality, and can be gamed. People game it.

- Step 4: David Graeber writes a blistering critique of your system. “If you want to minimize the possibility of unexpected breakthroughs, tell [people] they will receive no resources at all unless they spend the bulk of their time competing against each other to convince you they already know what they are going to discover.” [2; italics added]

The Riddler is quite proud of this 4-Step Process, and thinks it may be universally applicable - or at least applicable to his opening problem. “We have finite [vacancies in our partner corporations] and lots of [students who want those jobs]. We’ll have to create a systematic evaluation that impartially allocates this commodity. Ah, I know, we can give them grades!”

And there’s a Step 5 which emerges from bureaucracies like this. As Graeber put it,

The algorithms and mathematical formulae by which the world comes to be assessed become, ultimately, not just measures of value, but the source of value itself. [2]

In other words, after establishing some system of measurement which corresponds but meagerly to the real world, the bureaucracy affects an Orwellian inversion, and argues that what it’s measuring is what we should really care about.

You’d think this would be easy enough to resist. One has only to say “No, I don’t think what matters in education is giving students [grades].” But a side effect of bureaucracies is that, through sheer boringness, they create a vacuum of value surrounded by a miasma of jargon like efficiency and rationality. This is hostile terrain to common sense, and so we very often (trying, perhaps, to seem sophisticated) adopt the bureaucracy’s stated values as our own.

So, there we have it. The Riddler would synopsize Graeber’s position on evaluations like this: in a post-war administrative high, the U.S. over-applied the corporate management techniques it had used to win the war, and grafted lumbering bureaucratic standards onto academia. Resulting from the imperfect evaluations it devised (e.g. grant applications, tenure committees, grades) came both surges of people trying to game the system (e.g. Mastroianni’s students who told their teachers about their digestive distress), and generations, acclimated to the bureaucracy, who insist that those evaluations have intrinsic value.

A particularly resonant idea from “The Utopia of Rules” is that there’s a Gödelian impossibility at the heart of any system of rules or incentives. It can never completely achieve its goals. Any set of rules will always have exceptions, special cases, needed revisions and shortcuts. Any evaluation will always have outliers, who (like Oppenheimer) might try to murder his experimental physicist advisor but can go on to lead the Manhattan Project, or are (like Newton or Heidegger or Norbert Weiner) obnoxious interpersonally but too brilliant to ignore. Under the old system, these exceptions were made routinely, usually by colleagues with an excellent intuition for scientific valor, and a tolerance for eccentricity.

But this new system of seemingly complete and impassable rules affects a neat vanishing trick, where the administrators of such a system appear to have eliminated the human responsibility of making touchy-feely exceptions, replacing them with cold, hard rationality.

Graeber wasn’t fooled.

Always remember it’s all ultimately about value: whenever you hear someone say that what their greatest value is rationality, they are just saying that because they don’t want to admit to what their greatest value really is.[2]

Look back a few paragraphs. “Under the old system, these exceptions were made routinely, usually by colleagues with an excellent intuition for scientific valor, and a tolerance for eccentricity. ” These, the Riddler notes, are values – chiefly an appreciation of scientific originality coupled with a general disregard of character flaws. They may not be good values – but they have two traits the Riddler much admires. They are clearly stated, and are clearly domain-specific.

Contrast that with the milquetoast blend of ‘rational, impartial evaluation’ we are told the grading system achieves (or aspires to). What are its values-behind-the-curtain?

Academic excellence? Nope, as that really just means “getting good grades”, and is circular. Engagement with the classroom material? Nope, not really, just the parts that will appear on the tests. A love of learning? Certainly not; it gives students lifelong nightmares.

How to cynically manipulate the system to get ‘A’s by gaming the problem sets, cramming the indicated topics before each exam (likely forgetting them soon after), and inducing your professors’ empathy by telling them about your stomach ailments?

!…!

The Riddler doesn’t really know how to fix this, or how to design ungame-able evaluations. Indeed, he rather suspects this is impossible. He’ll only offer the possibility that, sometime in the late 20th century, we began to put too much faith in systems and too little faith in each other, and that reversing this trend might be the Riddler’s best shot at getting the transmogrifying teleporter of his dreams.

Fortnightly Riddles

Johnnie’s gym teacher has, as an exercise in minimalism, done away with the class dumbbell set and replaced it with a combination of four ring-shaped weights, a pulley, and a length of rope. He claims that with strategic use of these materials, his students can exercise themselves with weights of any integer amount less than or equal to 40 lbs.

What four weights does he have?

Solve it? Post your answer as a comment to this newsletter to claim credit : )

That’s all for now. Thank you for the gift of your attention.

Kincaid & the Riddle Team