Riddle Fortnightly No. 12

Of the 18th of November, 2024

Fortunately, the continuity of spacetime has resumed: the Fortnightly is back!

In this edition, we have a round up of new E-ink and time-blocking tools, then an (unusually long) column with the Riddler’s take on “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books” (It involves prehistoric horses and poetry). Plus, of course, another Johnnie Problem.

So sit back with your favorite e-reader (or, if you’re reading this via email or on the web, ship it off to a more comfortable location), get out some tea and biscuits, and enjoy!

Kincaid

Thinking Tools

Apps, tools, and workflows for thinking better with technology.

We’ve shared a couple of workflows on Riddle that feature quite specific tools. But while workflows should probably seldom change (and even then, only evolve slowly), the landscape of tools is evolving quite rapidly. With that in mind, here are a few new tools that fit quite nicely in our E-ink centric workflows.

1. BookFusion - a worthy Readwise Reader competitor for long-form content

Many have recommended Readwise Reader for android e-ink tablets and e-readers (like the Boox). But Reader is, foremost, a ‘read-it later’ service, made for digesting articles from the web – it struggles with longer form content like PDFs and epubs (frequently, while reading ‘Crime and Punishment’ on my Boox Page, the app spontaneously froze and crashed).

BookFusion has many of the same niceties as Reader (optimizations for E-ink tablets; the ability to sync highlights to Obsidian), with a more performant android app, and many extra power features that even Reader lacks. For instance, highlights taken out of order (e.g. when revisiting some chapter after skimming it) are synced to Obsidian in the correct order. And in the android app, you can highlight figures in PDFs – something Reader only supports on iOS.

I’ve switched my longer-form technical content (textbook PDFs, epubs) into BookFusion, while keeping Reader for shorter articles.

2. Morgen Calendar - privacy-preserving time-block planning

A month back, I outlined a workflow for Exceedingly Efficient Time-Block Planning with Reclaim and ClickUp - Reclaim being an ‘AI calendar app’, ClickUp a web-based project management tool. Unfortunately, Reclaim was just acquired by Dropbox, which doesn’t bode well for its future… and ClickUp has always been both clunky for individual use and pretty expensive. Plus, this workflow required putting a huge amount of personal information into GCal. Google doesn’t mine that to build predictive models of your behavior, right?

There’s now an alternative. Morgen.so, a Swiss company, makes an (Electron) app that pulls tasks from various systems side-by-side with your calendar. It supports calendars from iCloud, Fastmail, and Google; and tasks from Todoist, Trello, ClickUp – and Obsidian, by building atop the Obsidian Tasks plugin.

Morgen has many of the same features as Reclaim – scheduling links, auto-blocked travel time – and recently announced an “AI Scheduling Companion”, which works how I always wished Reclaim would. You can define weekly ‘Frames’ (e.g. a block of ‘deep work’ time in the mornings), and Morgen will suggest tasks for each frame.

3. Llama 3.2 Vision - local handwriting to text

In A Marriage between Handwritten Notes and Obsidian, we described a workflow for auto-converting PDFs to transcribed Obsidian notes using a commercial API from Mathpix. I recently discovered that you can far higher quality transcriptions by turning the PDF pages into images and giving them to GPT 4o. But both methods require sending your handwritten notes off to some third-party server which, despite their promises, might be covertly storing it for training data…

Enter Llama 3.2 Vision, an 11B parameter model you can run on your computer (e.g. with Ollama). In my initial testing, it’s nearly as capable as Mathpix at transcribing handwriting and equations. I’ll likely be updating the ‘Penman’s PKM’ automation in the near future. In the meantime, I encourage serial tinkerers to look into this.

Elite Students, Great Expectations, and Eohippus

Quotes from ’round the web, collected by our resident spyder: the Riddler, whose grumbled commentary you’ll hear below.

- [RH] ”The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books”, Rose Horowitch, article pub. 2024 in The Atlantic. Link

- [CSM] “The Atlantic did me dirty”, Carrie M. Santo-Thomas, substack post pub. 2024. Link

- [CPG] Similar Cases, Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Poem. Link

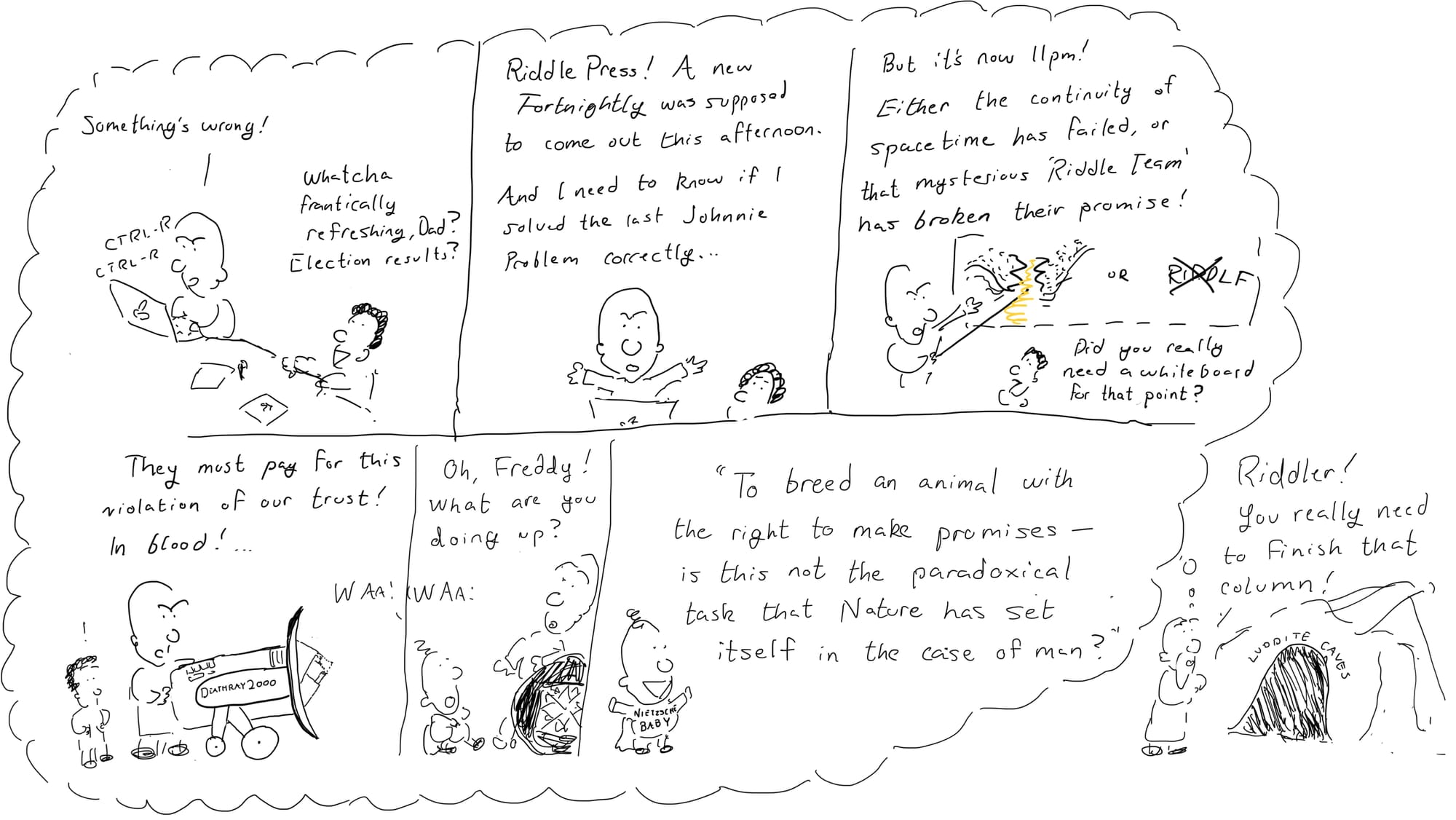

Oh dear. Another (couple of) fortnights has passed and the Riddler was too busy binge-watching ‘LUDD’ and scrolling through ‘Xs’ on X to prep for this week’s column. Some of them were XOXOs sent in appreciation of last month’s tirade against PowerPoint. Some of them were crude emojis with X’ed out eyes – “X_X” — presumably sent by the PowerPoint goons. Anyway, he’ll have to skim his assigned reading and do a little improvisation. Nothing a Riddler can’t handle.

Here goes… Ahem…

Rumor has reached the Riddler that the kids these days no longer know how to read books. This has, of course, been long suspected. Plenty of adults, after all, have traded in their novels for Netflix – and, even in 2006, Nicholas Carr wrote that reading was becoming “A quaint pursuit, like ballroom dancing or darts”. But here’s a troubling new piece of evidence: this growing illiteracy has now reached the highest echelon of brainy young Americans: elite college students.

At least, that’s what the Riddler gathered from the title of this week’s first selection, “The Elite College Students who Can’t Read Books.”

This is the sort of story we’ve seen quite frequently in the past few decades. and it always occurs in three acts. First comes the attention-grabbing wail: “PowerPoint is Evil!” – “Google is making us stupid!” – “Smartphones have ruined a generation!” – “Even Elite College Students Can’t Read Books Anymore!” Then comes the ‘cultural dialogue’ about that wail. Many are quietly unsettled, and some voice concerns – but they tend to be drowned out by ornery techno-optimist-fatalists who raise a hailstorm of counterpoints and contend that — even if the concerns had legitimacy — there’s nothing we can do about it anyway, so all you Luddites had best head back to your caves.

Finally, a very small number of the concerned actually do venture to the Luddite caves, where they find the Riddler, who begins to recite a poem:

There was once a little animal,

No bigger than a fox,

And on five toes he scampered

Over Tertiary rocks.

They called him Eohippus,

And they called him very small,

And they thought him of no value -

When they thought of him at all;

For the lumpish old Dinoceras

And Coryphodon so slow

Were the heavy aristocracy

In days of long ago.

Said the little Eohippus,

“I am going to be a horse!

And on my middle finger-nails

To run my earthly course!

I’m going to have a flowing tail!

I’m going to have a mane!

I’m going to stand fourteen hands high

On the psychozoic plain!”

The Coryphodon was horrified,

The Dinoceras was shocked;

And they chased young Eohippus,

But he skipped away and mocked.

And they laughed enormous laughter,

And they groaned enormous groans,

And they bade young Eohippus

Go view his father’s bones.

Said they, “You always were as small

And mean as now we see,

And that’s conclusive evidence

That you’re always going to be.

What! Be a great, tall, handsome beast,

With hoofs to gallop on?

Why! You’d have to change your nature!”

Said the Loxolophodon.

They considered him disposed of,

And retired with gait serene;

That was the way they argued

In “the early Eocene.” [CPG]

Apologies Luddites, that was odd. The Riddler wasn’t sure what a poem was doing in his stack of papers. But he only really had time to skim it. Perhaps it will make sense later on.

The Wail

Said the little Eohippus,

"I am going to be a horse!”

Here, Eohippus is played by the Atlantic columnist Rose Horowitch, sounder of this week’s wail.

Nicholas Dames has taught Literature Humanities, Columbia University’s required great-books course, since 1998. He loves the job, but it has changed. Over the past decade, students have become overwhelmed by the reading. College kids have never read everything they’re assigned, of course, but this feels different. Dames’s students now seem bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester. His colleagues have noticed the same problem. Many students no longer arrive at college – even at highly selective, elite colleges – prepared to read books. [RH]

Elite college students, in other words, have in the past decade progressed from being bright if sometimes lazy (for the Riddler’s college sources confirm: very few people ever do all of the assigned reading) to haplessly “bewildered” by the thought of reading multiple books. It’s old news, of course, that students are reading less than they used to —

In 1976, about 40 percent of high-school seniors said they had read at least six books for fun in the previous year, compared with 11.5 percent who hadn’t read any. By 2022, those percentages had flipped.[RH]

— “but surely,” one might content, “those 11.5% of high-school bookworms are the ones going to places like Columbia and taking Literature Humanities?”

Except that ~6 books a year, especially for a high-school student taking English classes, is not very many. The computing pioneer Alan Kay has said that, for someone trying to read an intellectually rich life, “Reading a couple hundred books a year is the bare minimum." (src). And it matters which books.

For years, Dames has asked his first-years about their favorite book. In the past, they cited books such as Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre. Now, he says, almost half of them cite young-adult books. Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson series seems to be a particular favorite. [RH]

Percy Jackson is a fine series (the Riddler much enjoyed it himself) – but it’s commonly read by elementary school students. So what happens when you go from reading a Percy Jackson-style book every few months to, as a college freshman, being asked to read The Iliad in three weeks?

One UC Berkeley professor, Victoria Kahn:

“It’s not like I can say, ‘Okay, over the next three weeks, I expect you to read The Iliad,’ because they’re not going to do it.”[RH]

Kahn’s students used to handle 200 pages of assigned reading a week without trouble. Likewise for Dames, the Columbia professor

Twenty years ago, [his] classes had no problem engaging in sophisticated discussions of Pride and Prejudice one week and Crime and Punishment the next. Now his students tell him up front that the reading load feels impossible. It’s not just the frenetic pace; they struggle to attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot. [RH]

And there’s plenty more anecdata like this:

The majority of the 33 professors I spoke with relayed similar experiences… Anthony Grafton, a Princeton historian, said his students arrive on campus with a narrower vocabulary and less understanding of language than they used to have. There are always students who “read insightfully and easily and write beautifully,” he said, “but they are now more exceptions.” Jack Chen, a Chinese-literature professor at the University of Virginia, finds his students “shutting down” when confronted with ideas they don’t understand… Daniel Shore, the chair of Georgetown’s English department, told me that his students have trouble staying focused on even a sonnet.[RH]

At least you, the Riddler’s readers, made it to the end of Eohippus.

Let’s review. Horowitch has shown us that:

- High school students are reading fewer books than they used to. ~90% of high school students seem to read fewer than six books a year. The top ten percent read ‘at least 6’.

- Based on one professor’s account, they’re also reading less demanding books (or enjoying and remembering the demanding books they’re forced to read than preteen favorites).

- And the majority of 33 professors Horowitch interviewed (all in the humanities, and across many selective colleges) relay stories of a decline in literary skills among their students.

A necessary counterpoint at this stage is that, in contrast to the provocative title, the claim here really isn’t that elite college students “can’t read books“, or even are struggling to read books – it’s that, in the sort of intensive literary programs where professors expect you to read the Iliad in two weeks (together, likely, with the first few books of Plato’s republic and Herodotus’ Histories), today’s college students are struggling more than they used to.

To be fair: many adults would also struggle with this pace. And, to be doubly fair: crotchety professors have a history of complaining about the kids these days.

But, in the context of point (1), we should expect such a massive shift in teenager’s reading habits to have downstream effects on their competence in college seminars. The question, in this case, is: what’s happening in high school?

Horowitch has a couple of theories. One of them, of course, is smartphones.

Teenagers are constantly tempted by their devices, which inhibits their preparation for the rigors of college coursework – then they get to college, and the distractions keep flowing. “It’s changed expectations about what’s worthy of attention,” Daniel Willingham, a psychologist at UVA, told me. “Being bored has become unnatural.” [RH]

But Horowitz also points to changes in the high-school english curricula. Over the last decade, many high-school English teachers have shifted from teaching Wuthering Heights and Great Expectations to… excerpts and TED Talks?

One public-high-school teacher in Illinois told me that she used to structure her classes around books but now focuses on skills, such as how to make good decisions. In a unit about leadership, students read parts of Homer’s Odyssey and supplement it with music, articles, and TED Talks. (She assured me that her students read at least two full texts each semester.) [RH]

Part of this seems to be a desire to be hip, modern, and – well, more multicultural than Wuthering Heights. Part of it may be attributable to a mania around standardized testing, in which all reading has been converted into the sterile format of “short informational passages, followed by questions about the author’s main idea”. Quoth one Boston teacher:

“There’s no testing skill that can be related to … _Can you sit down and read Tolstoy?_ ” he said. And if a skill is not easily measured, instructors and district leaders have little incentive to teach it. [RH]

The Cultural Dialogue

And they laughed enormous laughter,

And they groaned enormous groans,

And they bade young Eohippus

Go view his father’s bones.

One of Horowitch’s interviewee’s, that “public-high school teacher in Illinois” who paired excerpts from The Odyssey with music and TED Talks, wrote a lengthy critique of the article. Some of her points are quite fair. Any journalist covering this topic has incentives to highlight their more incendiary bits of evidence and gloss over the subtleties.

Frustratingly, despite the numerous examples I provided of students reading books cover-to-cover in my class, Horowitch opted to include only the unit that, like the original rhapsodes of the bronze age, I excerpt and abridge. Equally frustrating is that her article implies that I was forced into that decision in order to pacify floundering students or submit to the demands of standardized testing. [CST]

This teacher, Carrie Santo-Thomas, has a few of her own theories of what’s changed that might lead college freshmen to struggle with the Columbia Literature Humanities. For one, high school teachers like herself are teaching fewer of the dreary old classics of Horowitch’s focus.

Passing references to Moby Dick, Crime and Punishment, and even my unit about The Odyssey, confine literary merit to a very small, very old, very white, and very male box… As Horowitch points out, I am just “one public-high school teacher in Illinois,” but while professors at elite universities sound the alarm over Gen Z undergrads not finishing Les Miserables because they are uninterested in reading a pompous French man drone on for chapters about the Paris sewer system, my colleagues and I have developed professional toolboxes with endless other ways to inspire our students to read about justice, compassion, and redemption. [CST]

So if students don’t finish the Iliad, it may be less that they are unable to read long-form literature and more that they refuse to read that kind of literature.

And that’s a good thing, since Gen Z and Gen Alpha don’t cow to authority for authority’s sake. They simply won’t do things they don’t want to do, and I actually kinda love that. The rising young generations want texts that matter to them, that reflect their lives and experiences. So when we force-feed yet another vanilla canonical dust collector, and then complain that they aren’t playing along, it’s just not a good look for us. [CST]

Do the work of updating your syllabi to speak to Gen Z, and, Santo-Thomas says, they’ll happily read whole books.

Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone, Ibi Zoboi’s American Street, and David Bowles’s The Prince and the Coyote, are all complex, challenging, and substantial texts that speak to the interests and experiences of my students, so it’s not a fight to get them reading.[CST]

Moreover, finding books that speak to today’s youth isn’t just a matter of selecting appropriately interesting subjects – but, literally, finding books that speak a language comprehensible to Gen Z.

Linguistically, the dialect of English spoken by contemporary adolescents is rapidly moving further away from the vernacular of the canonical works we ask them to read. While this has always been true to some degree, social media and technology have sped up language evolution and widened the gap between English dialects. My students code switch into my spoken dialect to engage with me – something that I never had to do to communicate with my teachers in high school. So when I ask them to code switch further into the recesses of linguistic history to read Shakespeare, the struggle is real.[CST]

In short, American culture – and perhaps even American English – has changed. Any book, even a classic, becomes less relevant with time; perhaps the time is due to prune some of the Western cannon’s classics off of high school and college curricula to make room for modern classics, like A Long Way Gone (the memoirs of a child soldier in Sierra Leone’s civil wars), which portray the human condition in no less color than the old classics, while being grounded in things more relevant to today’s world. This transition is being accelerated by the unusually self-determined reading choices of Gen Z, and by educators like Santo-Thomas. After all, we can’t carry on reading Crime and Punishment forever!

This is a substantive issue, certainly suitable for lengthy debate. How long should we carry on teaching classics with such diminishing relevance to the modern world? The Riddler will only note here that a large part of the value of a classic, apart from its intrinsic literary merit, is that it has been widely read. You can bring up, say, Brave New World in conversation, and be reasonably confident your interlocutors will have heard of Soma or the Feelies. It’s a marvelously effective way to communicate – conveying, with a few words, ideas it took the author hundreds of pages to spell out.

Of course, this only works with people who have read the classics, which (thanks in part to educators like Santo-Thomas) is a shrinking number. People know Big Brother and Gatsby, but most probably won’t recognize Raskolnikov or Steerforth. And even if they do, making references to classic literature has somehow acquired a stench of elitism – perhaps because the people most likely to understand them were in the Great Books courses at Yale, Columbia or the University of Chicago.

But it seems to the Riddler that, aside from the somewhat frightening assertion that Gen Z has developed their own mutually-incomprehensible dialect of the English language, none of this explains Horowitch’s main finding. If students weren’t reading the Classics because they were ideologically opposed to all that stuff from old-dead-white-males and not afraid to say so, why wouldn’t they express this to their professors? Instead, they’re telling professors like Dames that “the reading load feels impossible”, and that they don’t feel adequately prepared.

A first-year student came to his office hours to share how challenging she had found the early assignments. Lit Hum often requires students to read a book, sometimes a very long and dense one, in just a week or two. But the student told Dames that, at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.[RH]

This student may be an outlier. Perhaps many had teachers like Santo-Thomas’ and her diverse syllabi. But, when asked to name their favorite book, why would they cite Percy Jackson and not The Things They Carried? Why, for that matter, would they have “a narrower vocabulary and less understanding of language”? Presumably American Street is as or more effective at furthering these as Dickens. And, above all, why would the percentage of students reading at least half a book a month have declined from 40% to 11% over the last fifty years? Culture wars spring eternal. Students have a long history of rebelliousness. Surely, the Riddler can surmise, the only thing that has changed teenager’s lives enough to account for all of these strands is…

The smartphone.

Santo-Thomas really doesn’t like where this is going. Villainizing smartphones is “a move as cliche as blaming standardized testing,” she writes.

…a constant classroom annoyance to be sure, but old news, at least among high school educators, who have already read The Anxious Generation, adapted our routines, and moved on. It seems too easy of a target to take seriously in the context of a major American journal like The Atlantic, but here we are. It should go without saying that there is a medium between TikTok and Tolstoy. [CST]

She continues,

My primary concern throughout the summer of interviews, emails, and fact-checking, was that we were slipping into a familiar panic in the face of progress: how will this next technological or social development bring about the downfall of society? It’s an old story; in the fall of 1978, The MATCY Journal published a handful of “probable” quotes from history including the infamous lament over the proliferation of paper: “Students today depend on paper too much. They don’t know how to write on a slate without getting chalk dust all over themselves. They can’t clean a slate properly. What will they do when they run out of paper?” This, and the other quotes in the article, aren’t actually real. However, they reveal a genuine pattern in panicked thinking that, rather than unveiling flaws in social and technological change, instead lays bare the atrophied mindset of the people doing the panicking. [CST]

Hear that Luddites, with your atrophied mindsets? You’re old news. People have complained about technological change for millennia – and, so far, they’ve always been wrong.

Retreat to the Caves!

Said they, "You always were as small

And mean as now we see,

And that’s conclusive evidence

That you’re always going to be."

The Riddler likes Santo-Thomas’ coinage about finding a medium ‘between TikTok and Tolstoy’. He only wonders whether the mere existence of as something as addictively engaging as TikTok tips the scales uncomfortably towards distraction. Sure, we spend most of our lives in between the extremes – but shouldn’t a high school English classroom be one of the (few) places trying to tip the scales back towards Tolstoy?

Santo-Thomas doesn’t think the scales can be tipped.

If we position ourselves as fighting against social media and short-form entertainment, we’ve already lost. The dopamine hit from the ding of a push notification is far more neurologically satiating than anything I have to offer in a classroom. So even as I continue to develop more engaging curricula, I ask my students and their caregivers to reframe their expectations, to reconsider the type of “entertainment” that they expect from my class.[CST]

Back in 1984, Neil Postman warned that television was lulling us into the belief that anything worthwhile should be entertaining. Forty years later, high school english teachers are now faced with the delicate challenge of maneuvering their students out of this belief. As Santo-Thomas says, “if we position ourselves as fighting against [TikTok], we’ve already lost.” But how to compete? – for there is a zero-sum attentional contest between the book and the smartphone, and the smartphone is winning.

One strategy is to try to make your literature class more engaging, by centering the reading around themes relevant to the kids’ lives, inserting TED Talks, and recreating the vibe of Hank Green’s YouTube channel. “When my students shift their mindset to enter my classroom expecting nerdery, thought-provoking conversation, and midwest dad jokes,” she notes “they find that the forty-five minutes passes enjoyably.”

This seems, to the Riddler, about the best one can do. Were he a high school student taking English classes, instead of an immortal word-spinner, he would be privileged to have such a teacher as Santo-Thomas. She’s clearly thought deeply about how to do her job.

But she admits: the job has changed. For previous generations, English class was a bastion of stuffy old classics. The teacher presented Wuthering Heights; the students read it – many only under the threat of an ‘F’, but enough out of genuine enjoyment that teachers could live with themselves.

This worked, in part, because, as Santo-Thomas writes, “previous generations turned to reading as a leisure activity, so they had an innate sense for how to read in school and how to read sneakily under the covers way past bedtime.” Enough kids entered English class with a love of books that teachers could simply channel and refine their existing passion. That’s changed. “To some degree, all of the things I’ve mentioned in this essay have stripped reading of its human value and made it into a chore,” she concludes. “Teachers are thus charged with retraining kids to love books.”

The dialogue continues...

RIDDLER: Whew, this was a long one, folks. The Riddler does have to admit: he only made it this far by skimming.

But he thinks he can see the ingredients of a consensus. Horowitch says that the kids aren’t reading as well as they used to, which (given the raw statistics) seems pretty plausible. She gestures somewhat sheepishly to smartphones (aware how overused that point is); but directs most of the causal energy at the way standardized testing has caused some high school english teachers to rely on packets instead of books.

Santo-Thomas, one such English teacher, disputes that either standardized tests or smartphones are decisive factors. She contends that her classes read plenty of books cover-to-cover, but that teaching them requires different strategies than in the past. Branching out from the musty classics of the Western canon into more recent and culturally relevant books seems to help, as does making one’s classes more engaging while taking pains to reframe students’ expectations of entertainment. She agrees, sadly, that students don’t enter class with the same love of reading they once had.

Hmm. The Riddler had thought this was the conclusion. After all, he made it to the Luddite caves, but it appears he now has an audience, and must instead have entered another round of Cultural Dialogue.

ASPIRING LUDDITE: Yes, yes, I have a question!

RIDDLER: Go ahead.

ASPIRING LUDDITE: So obviously, digital media is the problem, right? If the underlying driver is that kids are no longer reading under their covers for fun, it’s because they’ve replaced books with iPads, right? And how can books compete, right?

ELITE COLLEGE STUDENT: Oh no, I disagree. I love books. But I love them too much. I know that when I start reading a novel, I won’t be able to stop myself from finishing it - so there’s four hours, gone. At least with Hank Green’s YouTube videos, I can entertain myself for 20 minutes and then be done.

SECOND STUDENT: Yeah, I love books, but they such have a high activation energy. I can’t get into the reading zone in just 20 minutes, so I end up browsing X’s on X instead. Oh, like this from @eohippus!

EOHIPPUS: LOL I’m going to be a horse!

THIRD STUDENT: And high-schoolers these days are so busy! In school from 8am-3pm, Speech and Debate and track practice from 3–5pm most every day, tuba lessons and symphony practice from 6–8pm, and two hours of homework afterwards. 20 minute blocks of leisure are all I had in high school, which is why I never read much during the school year, but then read six books in quick succession as soon as summer started.

RIDDLER: Well, those are interesting points which neither I nor either author noted.

ASPIRING LUDDITE: But it’s the smartphones right? Oh, and the high school English teachers are all giving their lessons in PowerPoint, which, as you so thoroughly demonstrated last time, must be making kids stupider than in the good old chalkboard and dust days!

POWERPOINT GOON: Die, Riddler, Die! X_X X_X X_X!

CORYPHODON: Socrates complained that the widespread use of writing would corrode our memories. Contemporaries of Gutenberg complained that ‘kids these days’ were spending too much time reading books. Every one of these end-of-times technological changes has come and gone; we adapt society, and human nature remains unchanged. Unfortunately, part of human nature is to mistake one’s growing senility for the decline of the world at large, hence the continued alarum!

MESOHIPPUS, 20 MILLION YEARS LATER: Wow, look how big my middle toe is now! I think I’ll call it a ‘hoof’.

CROTCHETY OLD PROFESSOR: Kids these days don’t pay attention in my lectures anymore. They all bring their laptops out and put their screens between their eyes and mine, and I think they’re checking email.

E-INK ENTHUSIAST: The trouble clearly is that many high school classrooms now channel their assignments (including assigned readings) through Google Classroom, which kids access on cheap chromebooks with awful flickering screens that make sustained reading painful. If only everyone bought these marvelous devices with paper-like screens!

CROTCHETY YOUNG PROFESSOR: Kids these days don’t pay attention in my lectures either, but I’m afraid of being called a ‘laptop nazi’ if I try to do anything about it.

E-INK ENTHUSIAST: Well, I think you should try something - just as an experiment. Ban laptops, but permit iPads and E-ink tablets. I think many students are similarly frustrated with their classmates’ use of laptops in class…

CORYPHODON: But you’d have to change their nature!

FIRST STUDENT: Yes, I’d like to see you try – it’s awful! Even when I’m trying to pay attention to the lecture, my eyes are continually diverted by this flashing as classmates in front of me CMD-TAB between Gmail and WhatsApp and shopping sites and the google doc where they’re trying to take notes. Once, during a cognitive science lecture on attention, I even saw someone open reMarkable.com and order an E-ink tablet!

E-INK ENTHUSIAST: Alright!

RIDDLER: Well, thank you everyone for coming out… There seems to be no end to this debate, which perhaps is an instructive moral: no one can predict where we’re going, or how we’re going to get there – only the general direction we want to go, and what immediate steps we can take to get there. Perhaps, with time, that’s all we need.

10 MILLION YEARS LATER

PARAHIPPUS: Guys, I’m a horse now!

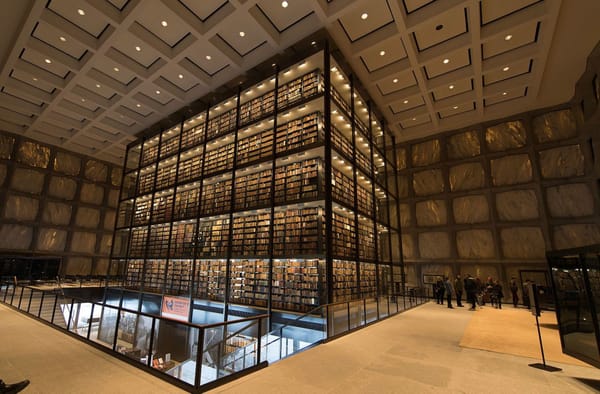

Fortnightly Riddle

The school’s Library Overlord is shelving an infinite supply of books with widths uniformly distributed between O and 2 inches, but in random order.

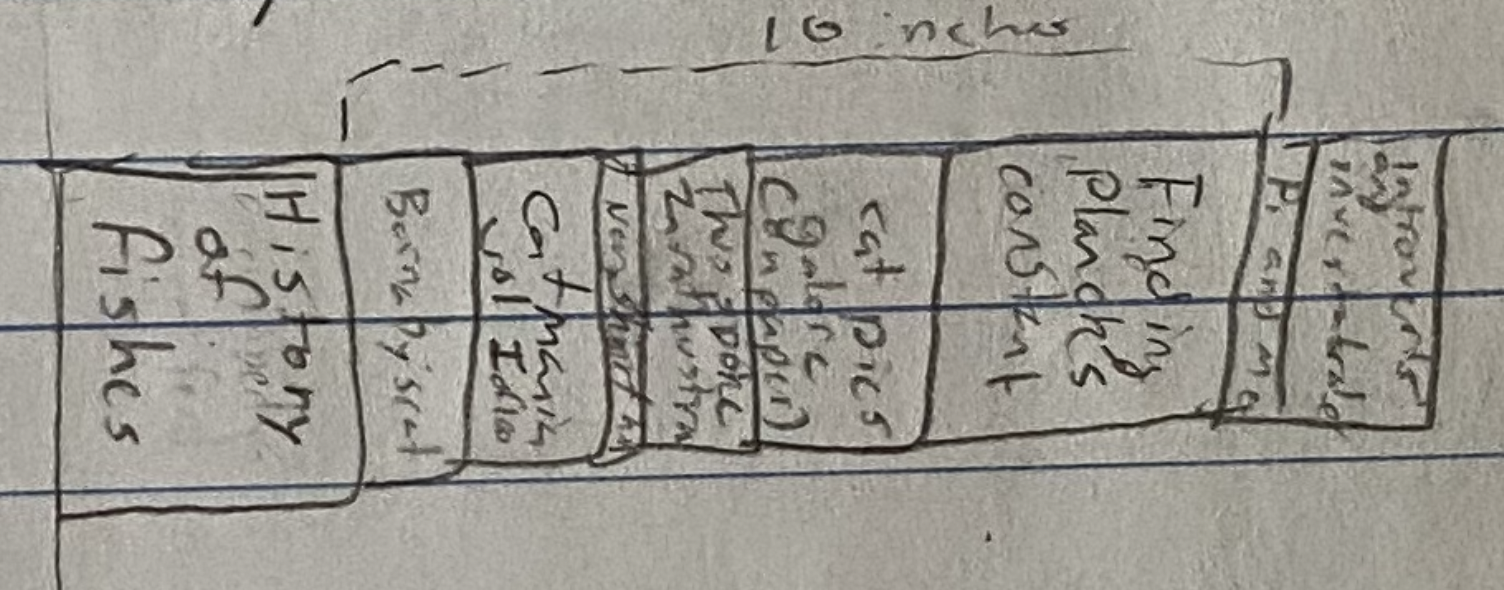

Johnnie’s evil math teacher ambushes the Library Overlord with a question. On average, how many books must be shelved before you can find two books where the distance between them (from the end of first to the beginning of the second) is exactly 10 inches? Assume infinite shelf space.

Solve it? Post your answer as a comment to this newsletter to claim credit : )