Riddler's Book Review: How the Information Age's New Elite were founded on a paradox

A quarter century ago, David Brooks wrote "Bobos In Paradise: the new elite and how they got there". The Riddler asks: what's happened to them since?

This is a review from the Riddle Book Club. Every few weeks, we read a book and write a small piece about/inspired by/in counterpoint to it. You needn’t have read the book to read this review - it will summarize the parts of the book that most struck us; but if some part of the review resonates with you, you probably should read the book.

This edition is about:

David Brooks - “Bobos in Paradise: the new upper class and how they got there”, short book, pub. 2000. Bookshop.org Link A (sometimes bitingly) humorous examination of the cultural changes brought on by the Information Age, and the contradictions therein.

This review first appeared in the Riddle Fortnightly, episode 10. You can subscribe to the Fortnightly at the top of the page.

The Riddler has a question for the youngen’ out there. Does anybody print things these days? If not, he has a contention: you’re missing out.

You see, printing things is one of the Riddler’s favorite activities. Blogs, essays, comic strips, ebooks, paintings from the Google Art project, and – when he’s feeling frisky – infinite-scroll webpages. All have passed through the Riddler’s Mammoth printer with an air of conquest and that pleasing cha-cha-cha-cha sound the Riddler takes as the sonic representation of information being made physical.

(Incidentally, the Riddler also has a 3D printer, but uses it far less. One can only have so many figurines of Ned Ludd.)

Printing is also the best metaphor the Riddler could come up with for the central theme in David Brooks quarter-century-old bit of social commentary, Bobos in Paradise. ‘Bobos’ stands for “bourgeois bohemians” – it was a cute acronym Brooks’ reviewers optimistically forecast would join the American lexicon alongside terms like “hippie.” As best the Riddler can tell, that hasn’t happened. Perhaps because many Americans aren’t clear what exactly ‘bourgeois’ or ‘bohemian’ really mean.

‘Bourgeois,’ as Brooks (and Marx) use it, refers to that tier of the upper class just below the aristocracy. In Marx’s day, the bourgeois were shopkeepers, accountants, big-company managers; they went to Harvard and Yale (because their fathers had), and though they were competent managerial professionals, they abhorred ‘eggheads’ and didn’t try to seem intellectual. Instead, they advertised their hereditary significance with conspicuous consumption: giant houses with parlors, gaudy, expensive furniture, jacuzzis and yachts. You see them in The Great Gatsby, or in the character Homais in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary.

‘Bohemians,’ as Brooks points out, have typically represented the antithesis of the bourgeois. They are the Romantics; they glorify artists living in poverty, following their passions, experiencing fully the joys of the ‘simple life’. They are also the hippies, the disruptive anti-institutionalists who shake their fists at ‘the Machine’ or ‘the System’ – systems run by the bourgeois. Throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s, the two camps seemed on the verge of a class war.

Then, mysteriously, the war ended - with no clear victor. Instead, the bourgeois and the bohemians merged – into the “Bobos”, our current upper class. Conspicuous consumption is now out, environmentally-responsible minimalism is in. Wearing tuxedos and going to the opera is out; the new upper class wears beaten-up jeans and listens to country music. Also out: being a loyal member of the ‘system’. Today’s CEOs act like bohemian visionaries and talk about ‘disruption’. Today’s Bobo employees view their work as an intensely personal endeavor – a source of meaning and personal fulfillment. If they don’t get it, they’ll leave. Bobos don’t like to think of themselves as an upper class, but they dominate our institutions (like The New York Times, Harvard, Yale, etc) and their values dominate our media.

This is a problem because, as Brooks contests, the Bobo values involve a paradoxical reconciliation of two opposing philosophies. And the source of that paradox may well be – cha-cha-cha-cha-cha-cha – the Information Age.

Writes Brooks,

The central feature of the information age is that it reconciles the tangible with the intangible. It has taken products of the mind and turned them into products of the marketplace. [1]

Or, as content ‘creators’ now call it, ‘the marketplace of ideas.’ As a consequence,

Just as the cultural forces of the information age have created businesspeople who identify themselves as semi-artists and semi-intellectuals, so nowadays intellectuals have come to seem more like businesspeople. [1]

In this framing, you can anticipate the self-righteous gong the Riddler probably overused in his last column. “Surely,” he might be about to say, “if intellectuals are turning into businesspeople, that can only portent ruinous cultural decay!” And the Riddler is very tempted to sound this gong, but then scrutinized it over more carefully, and realized that he’s not sure which way to hit it. Investors, CEOs, and the legions of regular businessfolk – they are all becoming more intellectual. Unlike the former bourgeois, with their contempt for Eggheads, they take ideas like environmentalism and social inequalities seriously. But this osmosis cuts both ways: the formerly austere and isolated intellectual class is becoming more commercially oriented.

So, should the Riddler strike his gong or not? On one hand, larger numbers of people taking an interest in the arts and sciences seems pretty good. It means more patronage (money!) for the poor, bohemian artists; more recognition (and money!) for the poor, overworked scientists, previously laboring in obscurity; more public engagement with relevant ideas and (money for!) those who publish them.

On the other, as Brooks suggests, all of this new interest (and especially the money) very easily corrupts the artists, scientists, and authors. It’s like a Columbian exchange. The much more numerous businessfolk (the bourgeoisie), trading with the fabled Island of Intellect. The businessfolk get lots of nice ideas, Malcolm Gladwell-style books like Outliers and The Tipping Point, packaged for commercial success – but the intellectual islanders are pulled into a capitalist maelstrom.

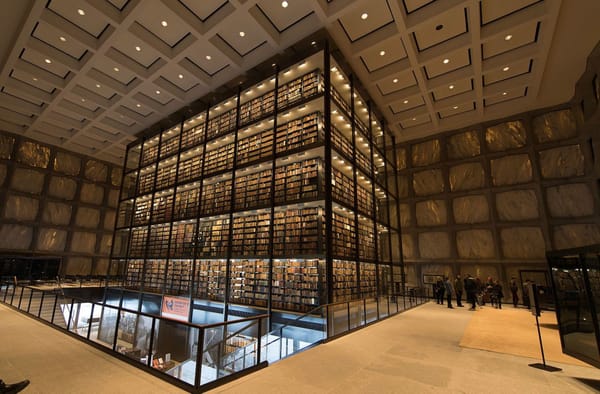

To illustrate this, Brooks gives a depiction of the pre-Bobo, pre-information age intellectual class. They were a snobbish bunch, aloof, contentious, and self-important:

Their memoirs are filled with intellectual melodrama: When Edmund Wilson published his review of so-and-so, they recount, we knew life would never be the same again — as if a book review could alter reality, as maybe in those days it could…

They considered themselves, and perhaps were, shapers of history. “A single stroke of paint, backed by work and a mind that understood its potency and implications, could restore to man the freedom lost in twenty centuries of apology and devices for subjugation,” wrote the painter Clyfford Still, apparently without being ridiculed. They went in big for capital letters. “These three great forces of mind and will—Art, Science and Philanthropy—have, it is clear, become enemies of Intellect,” Jacques Barzun declared in 1959, launching off into characteristically grand territory. And they issued the sort of grand and often vaporous judgments that today strike us as ridiculous. [1]

But these same traits that made them commercially unpalatable and generally unlikeable (even to each other) gave them the freedom to wax philosophic on a grand scale. They played with big ideas and offered grand theories, unhindered by the self-consciousness that, for today’s writers and thinkers, is perched censoriously on their shoulder. This had its advantages:

At the heart of this style was an exalted view of the social role of the intellectual. In this view the intellectual is a person who stands apart from society, renouncing certain material advantages and instead serving as conscience for the nation. Intellectuals are descendants of Socrates, who was murdered by the polis because of his relentless search for truth… They are influenced by the Russian notion of the intelligentsia, a secular priesthood of writers and thinkers who participated in national life by living above it in a kind of universal space of truth and disinterestedness, rendering moral judgments on the activities below. [1]

The Riddler will add that, though Brooks is concerned with the political contributions of these intellectuals, this same ‘universal space of truth and disinterestedness’ arguably applies even more strongly in the natural sciences. In mathematics, physics, or biology, many breakthroughs have come from Darwin, Poincaré, or Einstein-type figures chasing their own whims in isolation, without any commercial or reputational pressures.

Then came the Information Age. The internet and its kin kicked off that Columbian exchange with the Intellectual Island, and transformed the exchange of ideas from a secluded conversation among an aloof few into a bustling commerce. “A central feature of the information age,” Brooks writes “is that it reconciles the tangible with the intangible.” We all trade in information now. In so doing, we have “taken products of the mind and turned them into products of the marketplace.”

Cha-cha-cha-cha, goes the Riddler’s printer, still printing that infinite-scroll webpage. All those intangible, ethereal ideas from the intellectual priesthood, are being printed into something like dollar bills. What does the Riddler know? The Mind, entering the Marketplace! Isn’t that some contradiction? At the very least, as Brooks points out, it’s a radical departure. In the pre-Bobo days (e.g. the 1950s),

Commerce was the enemy of art. Norman Mailer got into a lot of trouble with his intellectual friends when his novel The Naked and the Dead became a bestseller. Its commercial success was taken as prima facie evidence that there was something wrong with it. [1]

But nowadays,

Intellectuals have come to see their careers in capitalist terms. They seek out market niches. They compete for attention. They used to regard ideas as weapons but are now more inclined to regard their ideas as property. They strategize about marketing, about increasing book sales. Norman Podhoretz was practically burned alive for admitting in his 1967 memoir, Making It, that he, like other writers, was driven by ambition. That book caused outrage in literary circles and embarrassment among Podhoretz’s friends. Now ambition is no more remarkable in the idea business than it is in any other. [1]

But while the Riddler is still hovering over his self-righteous gong, he pauses to reflect how many good things have come from this ambition to be popular instead of aloofly inscrutable like Kant. We have fewer Jacques Barzun-type sentences (“These three great forces of mind and will—Art, Science and Philanthropy—have, it is clear, become enemies of Intellect” – what does that even mean?) We have more Richard Feynman-like characters who, like Michio Kaku or Stephen Hawking, take care to make their ideas comprehensible to everyone. As a result, higher education is much more accessible; barriers to entry in fields like sociology or economics are lower. If the result is that some intellectuals develop a weakness for caviar and four-star hotels and spend more time trying to write best-sellers and appear on cable news shows and less time following their whims into unpalatable areas – is that really so bad?

Ultimately, Brooks comes out in favor of the new system. Some of the radical energy of earlier intellectuals has probably been lost. We’re a more conformist lot, more mindful of sales figures and resumes. But,

Today’s careerist intellectuals have a foot in the world of 401 (k) plans and social mobility and so have more immediate experience with life as it is lived by most of their countrymen. This grounding means that intellectuals have fewer loony ideas than did intellectuals in the past. Few of them fall for visions of, say, Marxist Utopias. Fewer idolize Che Guevara—style revolutionaries. On balance, it’s better to have a reasonable and worldly intellectual class than an intense but destructive one. [1]

This leads to Brooks’ unexpected (but convincing) argument that the Bobos, who are by-and-large culturally liberal, card-carrying Democrats, are actually conservatives in the mold of Edmund Burke. They value conservation – not only of land, but of their neighborhoods, and of the institutions they now run. And though they are the most educated upper class America has had,

they are not overwhelmingly impressed by the power of expertise. Instead, they seem acutely aware of how little even the best minds know about the world and how complicated reality is compared to our understanding. They know, thanks to events like the war in Vietnam, that technocratic decision making can produce horrible results when it doesn’t take into account the variability of local contexts. They are aware, thanks to the failure of the planned economies of eastern Europe, that complex systems cannot be run from the center. In other words, they are epistemologically modest, the way such conservatives as Burke… would have wanted them to be.

(Though the Riddler feels compelled to note that - in his day - Burke was considered something of a liberal. He supported American independence and their democracy project because, to him, it seemed well thought-out. He raged against French independence and in favor of the monarchy because he didn’t think it well thought-out.)

In other words, that fusion of the information age – that convergence of products of the mind and the marketplace – has tempered both. Gone are the intellectual radicals like Marx, who, after spending years locked in the basement of the British Library, emerge with new intellectual frameworks that spark decades of conflict. Gone also are the spurts of raw physical greed that arguably compelled colonialism and perpetuated slavery. The Bobos have achieved a great balancing act.

And this all sounds fairly reasonable until Brooks writes,

For the first time since the 1950s, it is possible to say that there aren’t huge ideological differences between the parties. One begins to see the old 1950s joke resurface, that presidential contests have once again become races between Tweedledum and Tweedledumber. Meanwhile, the college campuses are not aflame with angry protests. Intellectual life is diverse, but you wouldn’t say that radicalism of the left or right is exactly on the march.

“Why,” one might ask the Riddler, “are you thinking about a book published a full quarter century ago? Times have changed, man.”

To which the Riddler can only respond: have they?

One thing is for sure. Printing is a vanishing art. The Riddler will shed tears over this. If, at the turn of the century, the information age was realized through Epson laser printers, this last remaining bridge between the physical and digital has now fallen. The information age is now realized through tweets and tiktoks flying between iPhones. Brooks wrote of the reconciliation of “the tangible with the intangible”. Now, the intangible has, again, become mostly intangible - only glimpsed, briefly, poked at through a little touch screen, before disappearing amongst the flood of novelty that occupies our days.

The Riddler suspects this has something to do with how radically we’ve diverged from Brooks’ predicted future; how so many of the Bobos who tried so hard to be unpretentious were still swept up by ideological fervor, and how – despite communication being physically easier than it has ever been – the citizens of the U.S. have never had more trouble communicating with each other.

But one also notices, reading Brooks’ critique of the 1990s, how little our currents of thought have changed. The ideas that spewed from the Riddler’s printer back then are still spewing, just in 180-character sentence fragments and two-hour YouTube rants. It’s all there: the disillusionment with meritocracy, the tension between capitalist expansion and environmental conservation, the distrust of institutions, bureaucrats, and the “system”, even by those looking to run it. Our much more numerous and publicity-hungry public intellectuals have been passing around recycled fragments from earlier eras – except they, and their readers, are no longer so epistemically modest.

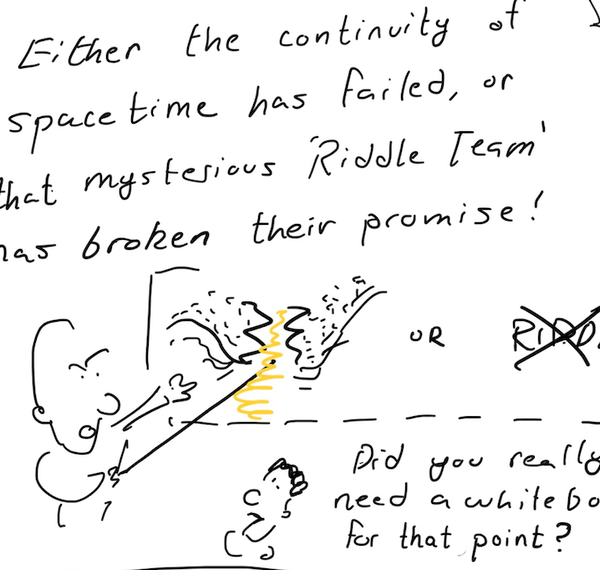

Nietzsche wrote that the cleverest writers “leave it to one’s reader alone to pronounce the ultimate quintessence of our wisdom.” Perhaps the quintessence of Bobos in Paradise, viewed in light of the past decade, is that the Bobos’ marriage of bourgeois and bohemian values never resolved its underlying contradictions. Those have been there all along, ignored but festering, and were all but fated to eventually cause that most hated sound of the Riddler’s printer –

A paper jam.